We need to question the underlying ethics. How often are students actually cheating? In an online survey of 128 students, 85 percent admitted to cheating one way or another. The most common form of cheating was copying homework, which was indicated by almost all respondents who admitted to cheating. But why are students cheating? Around half of respondents believe that the single greatest reason is due to large work loads, while 20 percent think itís due to pressure from home and another 20 percent believe itís because of a lack of confidence in knowledge and understanding of the material. Students are receiving all sorts of pressures to be successful, from school, home and society, which simultaneously act as pressures to cheat. Although cheating is inexcusable, the temptation is understandable.

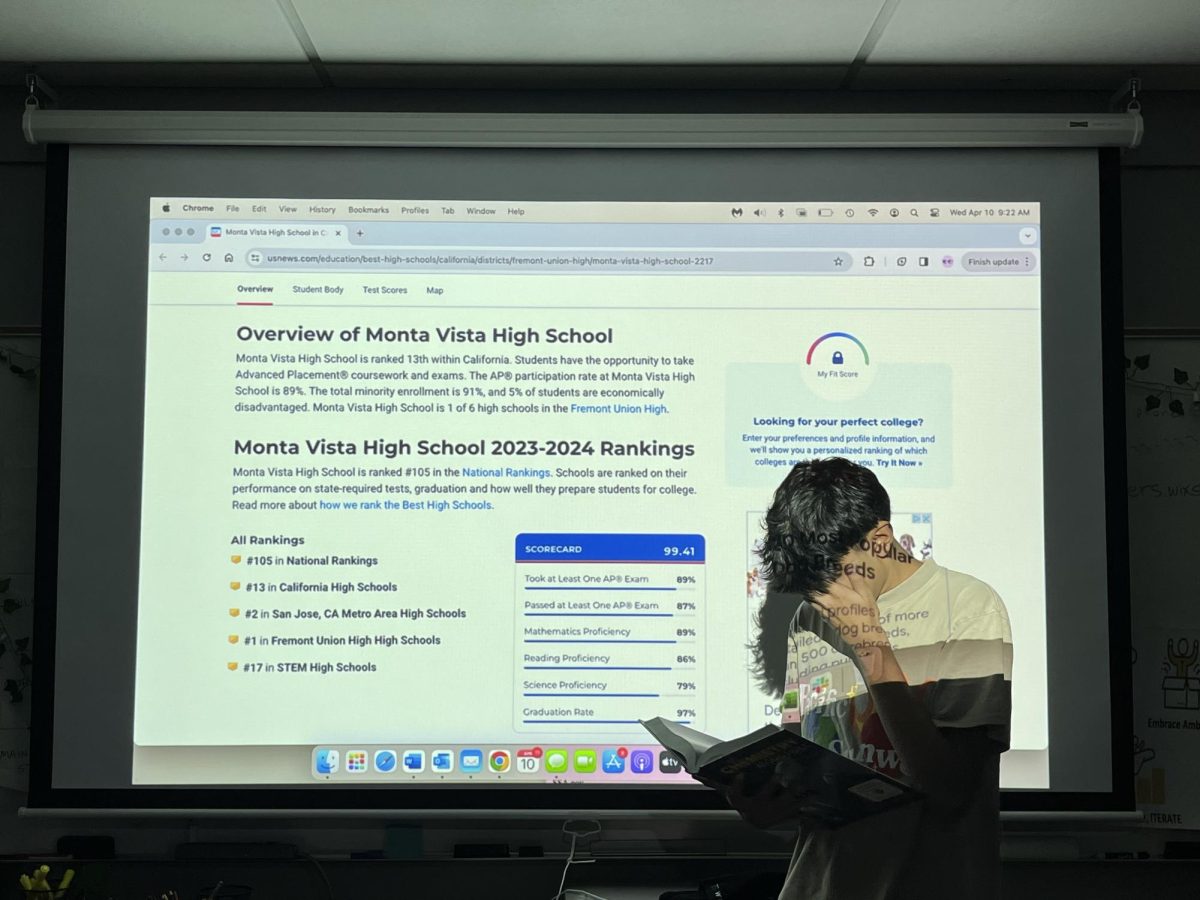

Not surprisingly, cheating and points culture are very much intertwined at MVHS; one fuels the other. Students at our school are notorious for doing whatever amount of homework weíre given, no matter what it takes, whether thatís an all nighter, using the answer key we found online, or asking a friend to copy their homework.

If we want to reduce cheating on our campus, we have to hit two birds with one stone. Letís stop only treating the illness, cheating, and focus on prevention: letís stop grading homework. Although discussing the ethics and consequences of cheating is important, itís not enough to tackle the issue. That might sound extreme to some, but ending the practice of assigning graded homework could provide many benefits for our school on top of reducing cheating.

Teachers assign homework for one main reason: so students grasp the material discussed in class. The goal is learning. The problem, however, lies in the points that are often tacked onto homework. MVHS students will complete any amount of homework assigned, but given their busy workloads, homework isnít about learning anymore. Itís about points.

It becomes a rush to get it done, to do the absolute minimum amount of work to still receive that stamp, possibly the period before itís due, possibly copying from another studentís homework. Anything for that stamp, that check mark, that A. Forget learning, and forget academic integrity. If teachers simply gave out the same homework, but awarded no points and set no deadlines for it, this problem would be relieved. In fact, 92% of respondents in a survey of 51 students said that they would be less likely to copy homework if it was not graded.

Even if we forget quality of work and the possibility of cheating, the case for homework isnít very strong. Studies have shown little to no correlation between homework and understanding. One study by Valerie Cool and Timothy Kieth in 1991 used data collected on high school achievement by another major study to analyze what factors and practices had the strongest effect on academic achievement. The study found that ìhomework had inconsistent direct effects [on academic achievement]î, which was measured through standardized testing.

Some studies have found a modest positive correlation between amount of time spent on homework and scores on standardized tests in math and science, but these are correlations, not causal links. Students that spend more time on homework are probably going to spend more time preparing for exams. At best, these studies tell us that the subjects are hard-workers, not that homework led to their academic success. As Alfie Kohn, a well-known lecturer in the field of human behavior and proponent of progressive education puts it, ìEven assuming the existence of a causal relationship… is [homework] really worth the frustration, exhaustion, family conflict, loss of time for other activities, and potential diminution of interest in learning?î Teachers might be well intentioned when they assign homework, but there simply isnít much empirical backing.

The benefits could even extend far beyond reducing cheating and a renewed emphasis on learning. We all know that students at MVHS often take up rigorous course loads, but thatís not something that can easily change in the foreseeable future. That would require a shift in campus culture. By not grading homework, students can be more flexible with their learning. They can choose when and even if to do an assignment, allowing busy students to have more control of how they budget their time. 88% of respondents said they get less than 8 hours of sleep a night, 89% of which indicated that itís due to their academic work loads. Students would clearly benefit from this much needed flexibility, especially in light of the fact that sleep deprivation is all too common at our school.

As a school, a divorce from the outdated concept of awarding points for homework would leave tremendous effects on our school. It would bring about a cultural change on campus that would emphasize learning and understanding, placing less of a focus on meeting deadlines and doing homework for the sake of points. In effect, fewer students will cheat day to day. If academic integrity and maturity is at stake, we should all be open to making this change.