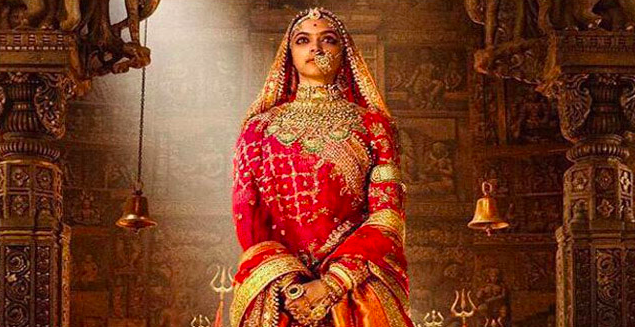

“Padmaavat” is a legendary Indian myth of the elusive queen, Rani Padmini, known as Padmavati in the film. She was deeply in love with and married to a brave Rajput king, Ratan Singh of the Mewar kingdom in Chittor. The two lived their peaceful lives until the Muslim leader, villainous Alauddin Khilji, set his eyes on Padmavati. The men fought to extreme lengths over her beauty, and ultimately Khilji was victorious in treacherously murdering Padmavati’s beloved husband. This story is most famously known for its climactic ending. Padmavati, rather than allowing Khilji to exploit her like some kind of conquest, commits suicide by burning herself alive.

I always feel some level of annoyance when my classmates and I inquire about each other’s family roots during a lull in the middle of class. You would be surprised at the number of people with absolutely no idea as to where I come from. My name, my skin tone and the actuality of my roots all contradict each other. Guess after guess, the answers amuse me endlessly. Who knew there were so many different kinds of Indians? North, South, East, West, Northeast, Southwest, this side of the river in that particular village — the list goes on. Yet none have come close to what I identify myself as. After the thousands of guesses, I finally disclose, “I’m actually Rajput,” and I’ve slowly gotten used to the response: “What is that?”

When I explain Rajputs to be a relatively higher level of caste in India, my sanity is immediately called into question. In our forward-thinking society, it’s rare for people of Indian descent to be defined by their caste, and I constantly receive judgment for identifying with mine.

As a forward-thinking girl in the States, how could I possibly stoop low enough to recognize the outdated caste systems of ancient times? I’ve never really seen what the big deal is, though. I feel an enormous amount of pride coming from a line of kings and queens, or at least choosing to believe that I do, without belittling other levels of castes. This is why, upon the release of the new Bollywood film, “Padmaavat,” I was instantly intrigued.

When I first heard of its arrival, I was mesmerized — however, much of India was not. Uproars of discontent circulated throughout the nation regarding the film’s alleged depiction of the Rajput Queen.

I was deeply confused as to why Indians all over, including my father, were so deeply offended by the production of the film before it had even come out. None of the reasons I had heard seemed grave enough to ban the movie, which was what was being urged to do all over India. Was the idea of the actress playing Padmavati’s stomach being shown through her sari that offensive? Was the idea of an alleged romantic dream sequence between Khilji and Padmavati so outrageous? Apparently so.

Despite my fellow Rajputs’ reactions, I remained blissfully waiting for the release of the movie, which to my dismay, kept getting pushed back due to protests all over India. The way I saw it, the film had found a way to incorporate my favorite cinematographer, music genre and actors all together, as well as glorify the lineage of my caste.

This movie was in all aspects made for me.

Unfortunately it didn’t take more than 15 minutes in the theater to realize how terribly mistaken I was.

Yes, the characters were all absolutely stunning in every aspect, especially Padmavati. But for the first two hours of the movie, she was just a pretty face and the source of all conflict. The directors might as well have named the movie “Khilji” as a result of the antagonist’s predominant importance in the film.

In no way did I feel as though there wasn’t an attempt to give Rajputs respect in the film. However, we unintentionally ended up being portrayed as complete imbeciles, lacking even basic common sense, arrogant rulers and close-minded racists, none of which come close to the reality of my caste.

The entire foundation of the movie was built on how Padmavati was so beautiful, even pious saints had improper thoughts about her. Even Singh’s spiritual teacher, who is a known saint, can’t help leering through her bedroom walls. He is caught and sentenced to banishment, in which he encounters Khilji and the two conspire to defame the Mewar kingdom.

The idea of such an occurrence infuriated me. This entire movie repeatedly shoved into the minds of the spectators that Rajput men are so ethically steadfast, they wouldn’t so much as dream of looking at the wife of another man. How on earth did Bhansali, the director, feel it was justified to portray Hindu saints in such a way, though? The only caste above Rajputs in Hinduism is that of the priests, and at the expense of glorifying Rajputs, he has absolutely insulted the cleanliness of Hindu saints, which to me was appalling. Above being a Rajput, I am a Hindu.

Another frankly insulting aspect of the movie was the sheer stupidity of the characters. Yes, we’re Rajputs who uphold our morals no matter what, but I can honestly say I’ve never been more agitated in a movie theater watching these Rajputs maneuver their way around the battlefield.

When Khilji gets word of the unreal beauty of Padmavati, an obsession takes birth, and he becomes ready to do anything to obtain her. He goes as far as “surrendering” to the Rajputs, in an attempt to sneak into Singh’s forts as a guest and wreak havoc. Singh is warned by Padmavati that this is all a conspiracy, yet he still accepts Khilji with open arms. During this encounter, he has several opportunities to kill Khilji, but refuses, informing him, “You’re lucky your enemy is a Rajput because to us, our guests equate with our God.”

Later on, Singh is again faced with a prime opportunity to kill Khilji, as he has already been laced with poison and can easily be brought down. Khilji even warns Singh, “If you don’t kill me now, you’ll end up regretting it.” Singh, however, refuses again, responding,“You’re lucky your enemy is a Rajput because we would never attack a defenseless person.”

I truly commend Bhansali for making Rajputs seem like the most virtuous people who ever lived, but how stupid did he think these characters were? Despite the intents, more than anything, Rajputs came across as self-righteous buffoons who were too stupid to attack. Thanks a lot, Bhansali. Sure, I was prideful to see how honorable Rajputs were, but seriously: above being a Rajput, I’m a logical thinker.

One of the most infuriating things I came across in the movie was how inconsistent Bhansali was with his depiction of Rajputs. One minute the Rajput characters are pure and virtuous, and the next they are cruel and selfish.

When Padmavati and her husband are in the clutches of the nefarious Khilji, Khilji’s wife ends up saving them, allowing them access to a secret tunnel for escape.

It was all very touching, but here’s what had my jaw dropping: despite the life-saving help they receive from his wife, they don’t do anything to help or protect her, leaving her to suffer a fate worse than death, solely because she was a Muslim. I was shocked at how Bhansali portrayed the conflict between Muslims and Hindus. Padmavati even goes as far as labeling it as “good versus evil.”

NO.

In no way did I find it acceptable that Bhansali had the audacity to write that into the script. In a modern day and age, Bhansali should have at least humanized Khilji, rather than promoting the idea that Muslims are ruthless animals. If this many people were upset because of the portrayal of Rajputs, imagine how many must be ashamed of the portrayal of Khiljis and Muslims. I’m all for honoring the Rajput legacy, but not at the expense of another religion. Above being a Rajput, I’m at least a human being.

Despite all that was wrong with this movie, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit I was in absolute awe of the ending scene. Alauddin Khilji spends every waking moment yearning to own Padmavati, or at least to see her face. When her husband is treacherously killed on the war ground, rather than allow Khilji to abduct her, she commits Jauhar, or the act of self-immolation (burning herself alive), along with every woman in Chittor.

She inspires each of them, saying, “Our bodies will become ash but remain immortal. The Rajput pride is in our principles and our self-respect. And this will be the biggest loss of Alauddin.”

This scene connected with my family on a personal level because my father’s great grandmother committed Jauhar after the death of her own husband. It moved me to tears how all Khilji wanted was to see her face, but she didn’t even give him the satisfaction. Despite conquest after conquest (he was also known as the “Alexander the Great II”), his biggest loss in life was never even seeing the woman he was desperately fighting for. I saw my own family history in this scene, and for a split second, was proud to be sitting in that theater.

I wouldn’t say the movie defamed Rajputs in anyway, but I still wouldn’t want to be defined by or affiliated with this story in almost every single aspect. Above being a Rajput, I’m a girl who experiences emotions, and in the case of this movie, those emotions were predominantly shame.