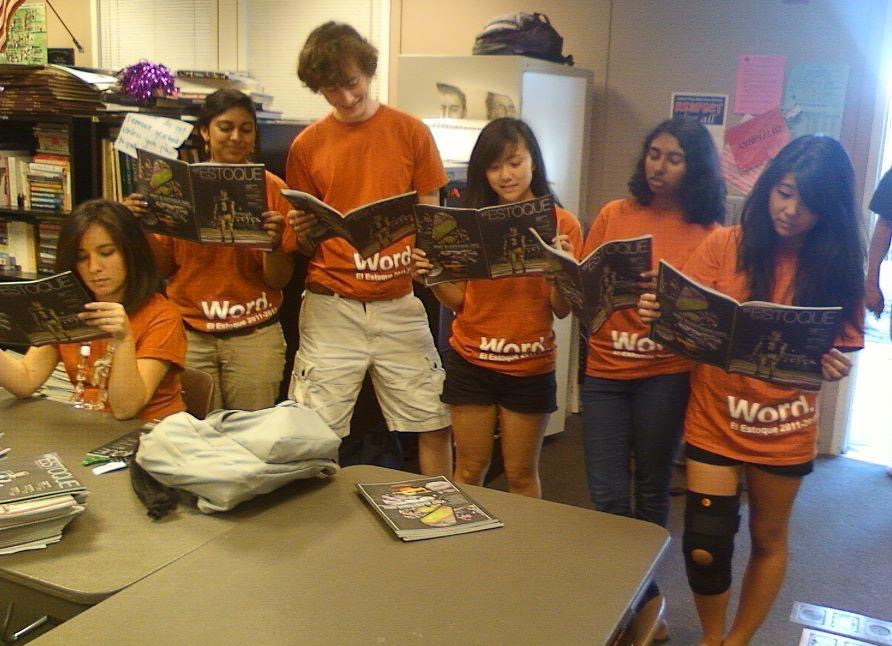

Privilege is like the air we breathe. We can’t see it, and we hardly, if ever, acknowledge its presence. Yet it is everywhere— in the top-notch education we receive, in the houses we live in, in our cars and our smartphones and our three meals each day. Many students don’t understand their privileges until after they leave school and venture off to college. Outside of the bubble of Cupertino, alumni begin to understand the differences in their educational backgrounds compared to students from other schools. Teachers, coming from different backgrounds, take note of how differently privilege is understood at MVHS in comparison with other schools.

AP Macroeconomics teacher Pete Pelkey

El Estoque: How did your perception of privilege change as you started teaching at MVHS?

Pete Pelkey: You guys are amazingly privileged in that you’re well fed, you’re well cared for at home… and that your sole responsibility is you grades. You guys, because your parents really value education, [they have] basically taken most of the responsibility off your plate, except for certain activities they expect you to do that will also enhance your resume. Because getting into that school is so important. When I was at Fremont, Homestead and Cupertino [High School], the lower socio-economic kids, you knew they weren’t going to college, they knew they weren’t going to college, it wasn’t even a possibility to most of them.

EE: What are some experiences you had with kids in other schools that you wouldn’t have had with someone at MVHS?

Pelkey: I had a young man over at Homestead who was going to be a welder. His goal in life was to be a welder. Because that seemed to be enough money for him to make, that was the expectation, he wasn’t expected to go anywhere, he was a working class kid from the other side of Sunnyvale. So he came to me one day, about eight weeks from graduation, and he said, “They’re going to let me into the welder’s union. But here’s the problem, I haven’t graduated high school yet, and I can’t wait eight weeks because my spot in the welder’s union goes. And if I don’t get in now, I’ll have to wait another year or two before my name comes up again. What should I do?” I went, “Well I think it’s obvious. You should drop out of school.” He said, “Well what about the education?” Then I went, “Then, you get the education, you go into welding, and that’s the best thing for you.” Well, I would never say that to a kid here.

EE: What is your experience with racial privilege?

Pelkey: Not at this school, but at other schools, I’ve had conversations with teachers who have told me that [their] grades for certain ethnicities are too high. “Why [should these kids] have Bs or As? They’re not going to go to college. Give them a C or a D.” Because that’s all they’re capable of. They give them a lower grade because they can, because Hispanic parents traditionally do not come and complain about their children’s grades. Black parents don’t come to school and complain about their children’s’ grades. And because in the teacher’s mind — this is an implication, they don’t say this — they’re not intellectually as gifted as other ethnicities. And therefore [they say], “Why do they have an A in your class? You must be giving that grade away.”

Industrial Technology teacher Ted Shinta

El Estoque: What about kids who don’t have the privileges that MVHS students have?

Ted Shinta: My friend was a teacher at a school near Sacramento. Unlike MVHS parents, parents from that neighborhood were not as well off and didn’t work to try gaining riches. Their detachment from their kids’ lives also led to kids that were harder to discipline and didn’t care to learn. He quit soon after joining because of the hardships he faced working in such an area. Because of this influence that students were forced to grow up with, many didn’t have any discipline and were a pain to try to teach. In fact, discipline that students from MVHS pertain is something that makes me and other teachers feel privileged to work here. It’s the dream job.

EE: What was Cupertino like when you were a child?

Shinta: I was a student at FHS. Neither of my parents had gone to college. Unlike now, at this time it was common that not many peoples’ parents had pursued a higher education. Therefore, this led to a disadvantage for me because my parents expected me to pursue a further education after graduating high school. Because my parents didn’t have much of a grasp of colleges, I was forced to find out information about colleges and how to apply and get in by myself, unlike how now many students at MVHS are privileged to have their parents know what to do every step of the way.

Math teacher Martin Jennings

El Estoque: What’s it like to be a teacher at MVHS?

Martin Jennings: Sometimes, it’s a drag. Students don’t want to get anything wrong, so they don’t take any time to figure stuff out and just quickly ask questions instead of thinking about it. However, I get to work with some of the most respectful students that are very interested in getting better at what’s in front of them.

EE: What are privileges that we have at MVHS?

Jennings: A lot of people don’t realize how safe MVHS is. At Independence High School [He worked at Independence High School], students bring weapons to school. There is a ten-member security team on campus that ride around in golf carts. Here, people don’t understand what a privilege it is to look in a mirror. There, mirrors are broken, vandalized and are covered with graffiti.

EE: What are the downsides of having the privileges that we have at MVHS?

Jennings: There’s a pressure that comes with studying at MVHS because many is brainwashed into thinking that there are only a few colleges that you can go to. This leads to a lot of emotional stress and students suffer. However, I know that they will all do well in college.

Class of 2012 alumna Medha Asthana

El Estoque: How has your perception of privilege changed from when you were at MVHS?

Medha Asthana: I come from Cupertino, a town that is very rich and very educationally privileged, and I knew that coming in. A lot of my expectations were that many of the people that I were gonna meet at this huge public university would have less educational privilege than I had. The resources that they were given weren’t as rigorous. [But] we don’t need privilege to be good in school. [MVHS students] have a heightened sensitivity to standardized scores, but other people don’t. One day in the dorm we were talking about SAT scores, and of course we were freshman. Someone said they got a 1400, and I was at 2250, and we ended up at the same school. It was just one of those “wow” moments. He’s doing really well in school and [he is a leader on campus].

EE: How has your educational privilege helped you in college?

Asthana: I was definitely better prepared for college … I’m getting a higher GPA without trying as hard as others who have a lower GPA.This disparity was most prevalent the first year of college. I know valedictorians, ASB presidents, who had 4.0s in high school, but had 1.0 GPAs in college, and they were kicked out. You may have a steeper learning curve in getting used to college, but … your will and your ambition can transcend privilege.

EE: Do you feel that you were more or less privileged than when you were at MVHS?

Asthana: When you look at the larger social concept. Being a woman, a person of color, it hasn’t changed. I still have socioeconomic privilege, I still have educational privilege. In college, I became much more aware of it, because I learned what these terms mean … I’m getting a larger scope. You don’t know what privilege is if everyone around you is privileged. Unless you have that collaborative conversation about awareness, then you won’t know what privilege even is or if you have it. In Cupertino, when everyone in the society is a privileged with money, you think that’s normal. But when you step out of that context … it gives you a wake up call.

Class of 2014 alumna Hana Hyder

El Estoque: How does your educational privilege compare to others’ in your university?

Hana Hyder: I see a dramatic difference. In MVHS, I got a lot of exposure with tech, and there are other people in the bay area that are involved in computer science programs in school that really motivated me to pursue this path, so we are really privileged to get the exposure. For students that lacked the variety of educational mediums presented in MVHS, they don’t know what interests them. School provided an opportunity to learn and gives MVHS students a sense of direction and a purpose.

EE: What are the downsides to having privileges in Cupertino?

Hyder: You don’t understand everyone else outside of our bubble. When I first arrived to UC Davis, we received a relatively easy assignment in computer programming. But, many in the class ran around trying to figure out how to do it. This confused me because even after a few weeks at computer science classes at MVHS, the assignment would be really easy.