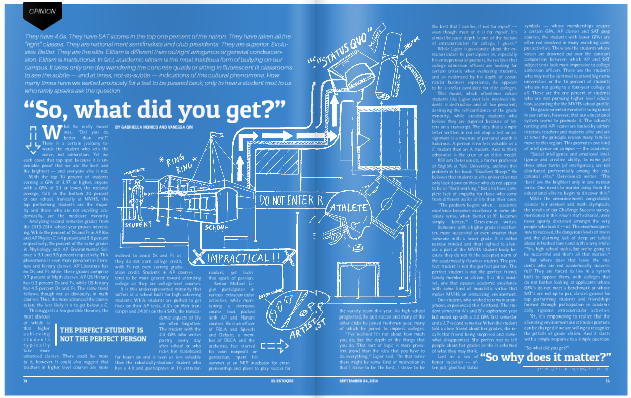

Elitism is different from outright arrogance or general condescension. Elitism is institutional. In fact, academic elitism is the most insidious form of bullying on our campus. It takes only one day wandering the concrete quads or sitting in fluorescent lit classrooms to see the subtle — and at times, not-so-subtle — indications of this cultural phenomena.

How many times have we waited anxiously for a test to be passed back, only to hear a student next to us, who rarely speaks to us, ask the question:

“So, what did you get?”

What he really meant was, “Did you do better than me?” There is a certain jealousy toward the student who sets the curve, not admiration. Yet we each covet that top spot because it is undeniable proof that we are the best and the brightest — and everyone else is not.

With the top 10 percent of students earning a GPA of 3.97 or higher, anyone with a GPA of 3.1 or lower, the national average, falls in the bottom 20 percent. The decile ranking is inherently a part of the grade elitism prevalent on our campus. Ironically at MVHS, the top performing students are the majority and those who are not excelling academically, are the mediocre minority.

Analyzing second semester grades from the 2013-2014 school year proves interesting. While the percent of Ds and Fs in AP Bio and AP Physics C is 4 percent and 5.8 percent respectively, the percent of the same grades in Physiology and AP Environmental Science is 9.1 percent and 9.8 percent respectively. This phenomena is even more prevalent in literature and history classes. AP Literature has 0 percent Ds and Fs while Myth has 9.7 percent Ds and Fs. AP US History has 0.3 percent Ds and Fs, while US history has 4.5 percent Ds and Fs. The same trend follows, though not as obviously, in math courses. Thus, the more advanced the course taken the less likely it is to get below a C.

This suggests a few possible theories, the most obvious of which is that higher achieving students take more advanced classes. There could be more to it, however. It could also suggest that teachers in higher level courses are more inclined to avoid Ds and Fs as they do not qualify for college credit with Fs not qualifying for graduation credit. Students in AP courses tend to be more geared toward attending college as they are college level courses.

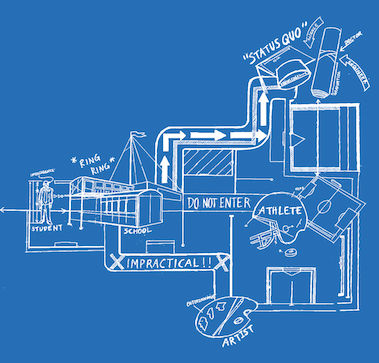

It is this underrepresented minority that suffers at a school built for high achieving students. While students are pushed by parents to get fives on their AP tests, 4.0’s on their transcripts and 2400’s on their SATs, the nonacademic aspects of life are often forgotten. The student with the 2.0 GPA who writes poetry every day after school or who rides her skateboard for hours on end is seen as less valuable than the robotically-studious student who has a 4.0 and participates in 10 extracurriculars, yet lacks that spark of passion.

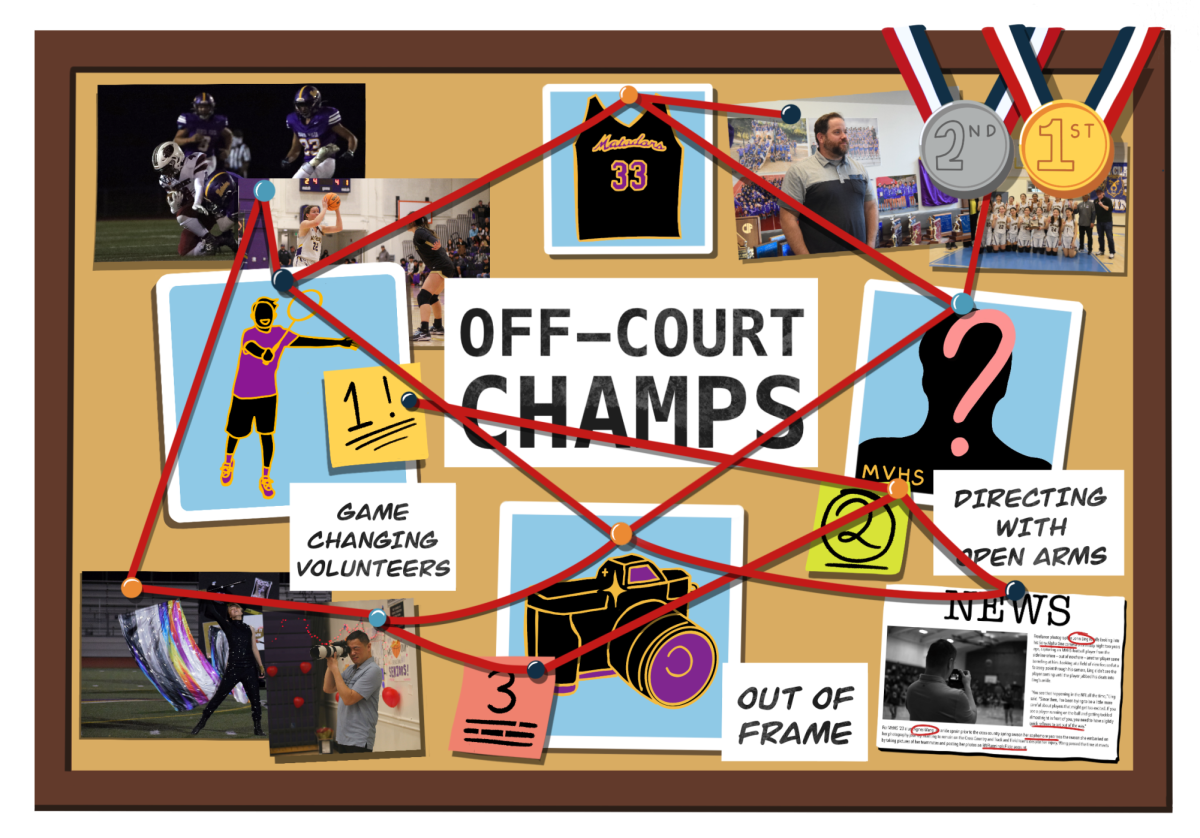

Senior Michael Ligier participates in various extracurricular activities, while maintaining a strenuous course load packed with AP and Honors courses. He is an officer of FBLA and Speech and Debate, a member of DECA and the orchestra, has started his own nonprofit organization, spent his summer at an MIT incubator for entrepreneurship and plans to play soccer for the varsity team this year. As high school progressed, he quit soccer and many of the other clubs he joined freshmen year, many of which he joined to impress colleges.

“I’ve realized It’s not about how much you do, but the depth of the things that you do. That sort of logic is more prevalent [now] than the idea that you have to do everything,” Ligier said. “In that sense there might be some kind of motivation in that I strive to be the best, I strive to be the best that I can be, if not for myself – even though most of it is for myself. It’s almost because depth is one of the factors of extracurriculars for college, I guess.”

While Ligier is passionate about the extracurriculars he participates in, especially his entrepreneurial pursuits, he realizes that college admission officers are looking for certain criteria when evaluating students, and as evidenced by his depth of cocurricular business experience, he appears to be a stellar candidate for elite colleges.

This model, which inherently values students like Ligier over students like our anonymous source, is destructive and all too prevalent, destroying the self-confidence of the grade minority, while creating students who believe they are superior because of letters on a transcript. The idea that a simple letter written in red ink atop a test or assignment is a measure of personal worth is ludicrous. A person is no less valuable as a C student than an A student. And to think otherwise is the crux of an elitist model.

William Deresiewicz, a former professor of English at Yale University, outlines this problem in his novel “Excellent Sheep.” He believes that students at elite universities not only look down on those who do not appear to be as “hard-working,” but also have complete lack of empathy for those who come from different walks of life than their own.

“The problem begins when… academic excellence becomes excellence in some absolute sense, when ‘better at X’ becomes simply ‘better,’” Deresiewicz writes.

Someone with a higher grade is not better, more successful or even smarter than someone with a lower grade. It is rather narrow minded and short sighted to alienate a part of the MVHS student body because they do not fit the accepted norm of the academically flawless student.The perfect student is not the perfect person. The perfect student is not the perfect friend, family member or citizen. It is this mindset, one that equates academic excellence with some kind of moralistic virtue that makes MVHS an ostracizing environment for students in the grade minority.

One student, who wished to remain anonymous, experienced this firsthand. The student aimed for A’s and B’s sophomore year but ended up with a 2.4 GPA first semester and a 2.7 second semester. When the student told a close friend about her grades, she recalls that friend being surprised and somewhat disappointed. She prefers not to tell people about her grades as she is ashamed of what they may think.

Lost in a sea of honor societies — often just glorified status symbols — whose memberships require a certain GPA, AP classes and SAT prep courses, the students with lower GPAs are often not involved in many enriching campus activities. These are the students whose voices are drowned out over the constant comparison between which AP and SAT subject tests look most impressive to college admission officers. These are the students who may not destined to attend big name universities or the 16 percent of students who are not going to a four-year college at all. These are the one percent of students who are not pursuing higher level education, according the the MVHS school profile.

The grade-oriented mindset is so ingrained in our culture, however, that our educational system seems to promote it. The school’s ranking and API scores are touted by administrators, teachers and students alike and are at times the principle reason many families move to this region. This promotes one kind of intelligence on campus — the academic.

“Social intelligence and emotional intelligence and creative ability, to name just three other forms [of intelligence], are not distributed preferentially among the educational elite,” Deresiewicz writes. “The ‘best’ are the brightest only in one narrow sense. One needs to wander away from the educational elite to begin to discover this.”

While the announcements congratulate science fair winners and math olympiads, the results of our Challenge Success survey, mentioned in this issue’s staff editorial, were never openly discussed amongst the very people who took it — us. The enormous pressure to succeed, the dangerous levels of stress and the alarming lack of sleep are talked about in hushed tones and with a wry smile: “Yes, high school sucks, but we’re going to be successful and that’s all that matters.”

But where does that leave the students who are not academically successful? They are forced to live in a system built to oppose them, with colleges that do not bother looking at applicants whose GPA’s do not meet a benchmark or whose SAT’s are not up to par, classes geared for top performing students and friendships formed through participation in academically rigorous extracurricular activities.

Yet, it’s empowering to realize that the alienating environment our attitudes promote can be changed if we are willing to recognize the pitfalls of grade elitism. And it starts with a simple response to a simple question.

“So what did you get”

“So why does it matter?”

This story was reported on by Gabriella Monico and Vanessa Qin