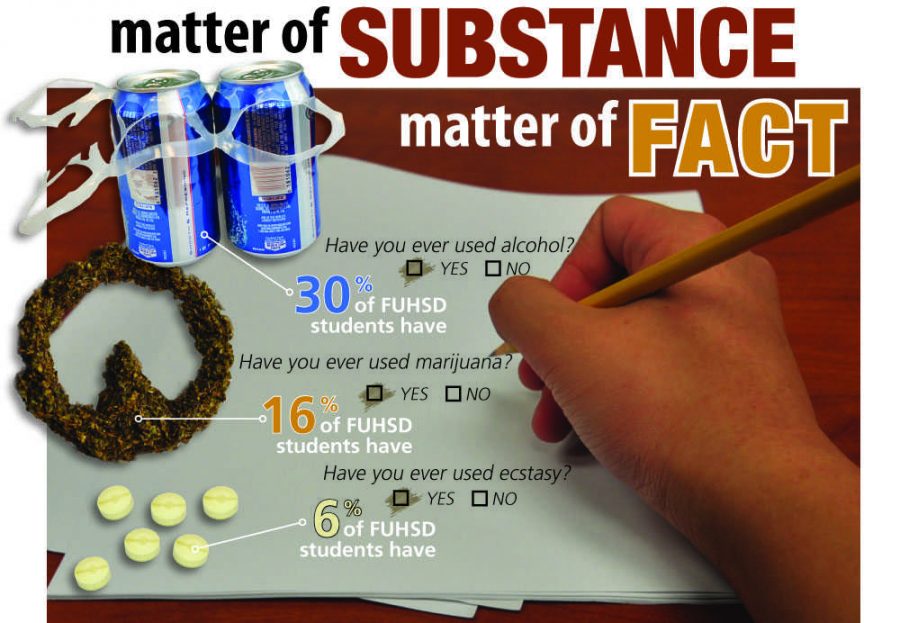

California Healthy Kids Survey reveals a third of FUHSD students have used alcohol or drugs. Is substance experimentation inevitable?

He takes a second, checks side-to-side for potential eavesdroppers. The sophomore male, speaking with El Estoque on the condition that his name would not be used, decides it is safe and starts to talk, his hushed voice muffled by the gusting wind.

He selected a deserted D-building corridor, with overhangs that offer scant shelter from the rain on this stormy March afternoon, as our meeting place, and for good reasons—reasons that an estimated 3,000 FUHSD students have in common. He recites them plainly.

“Drinking started freshman year. Weed started in seventh grade. Pills started freshman year.”

The rap sheet sounds extensive for a 10th grader, but it’s not unique. The sophomore is part of a group that makes up an entire third of students in the district: those that admit to using alcohol or illegal drugs.

Discipline and prevention

Administration is well aware of data like this, a statistic from the California Healthy Kids Survey. This comprehensive, biennial survey is administered to over 4,000 freshmen and juniors in the district.

In the 2010 rendition, 33 percent of FUHSD students claimed that they had used at least one substance from a list that included alcohol, marijuana, and other illegal drugs.

“I don’t think zero is reachable, but that has to be our target,” said Principal April Scott. “If that wasn’t our target, then all the things that we’re trying to put into place, the messages that we’re sending, and the interventions we have in place would be meaningless. The reason we have all these things is that we want [alcohol and drug use] to stop. And stop means zero.”

The issue was brought to the forefront in early March, after a senior was caught with an alcoholic energy drink known as Four Loko at the DECA State Career Development Conference. The episode was DECA’s second controlled substance incident at conferences in 2011.

Administration stepped in, as the student was suspended and permanently banned from DECA.

“My philosophy is not of a punitive mindset,” Scott said. “That’s not who I am. But we do have to think about it that way, unfortunately. We have to say, ‘If we really want a safe environment here on campus, then what are we going to do if students don’t provide that, and what consequences will there be?'”

MVHS also emphasizes programs that discourage substance abuse preemptively, including in-class health lessons, lunchtime activities that discourage smoking and substance abuse, and schoolwide assemblies.

Once students start [using drugs], there’s also the naïveté of, ‘Oh, I’ll just try it once and it’s not going to make a difference, and I’ll stop anytime I want,'” Scott said. “It’s certainly not that easy.”

The sophomore male disagrees, claiming that he can control his alcohol and drug use. Yet within a year of first using “weed,” it became habitual—he smoked two grams of marijuana, each and every day, by eighth grade.

He gives an easy explanation for why he started: “curiosity.”

“I had a cousin and older friends that did this stuff and they were completely fine,” he explained. “They were happy.”

Knowing people who have become involved in substance abuse, the sophomore male isn’t surprised that 33 percent of FUHSD students have done the same.

“That’s probably lower than I would’ve expected,” he said. “I know people that you’d never expect—people with straight As— that do harder stuff than me.”

In Scott’s mind, there is a very clear separation between alcohol and drug abuse, even though the two are so often lumped together. Although she strongly discourages experimentation with alcohol due to its detrimental effects on health, she views it as understandable because students grow up watching television commercials for alcoholic beverages and seeing their parents consume these beverages safely. The same cannot be said for drugs.

“I have a harder time getting my head wrapped around the drug piece, because it is not celebrated in the media, and it is not something that becomes a part of most homes and most celebrations,” she said. “So how students get involved with it, why they get involved with it, is a much more challenging problem to me. I think it speaks to the addictiveness of drugs.”

Budding teens, changing habits, different experiences

Also remarkable amongst the survey data is the difference between ninth and 11th graders; in the most recent results, this two-year gap corresponded to a drastic increase in those who have used alcohol or drugs, from 26 percent to 41 percent.

That statistic is understandable to one senior female, who also spoke to El Estoque on the condition that her name would not be used.

“The distance between an 18- and a 14-year-old is huge,” she said. “Becoming an upperclassmen kind of changes you… I think that’s a gradual experience that people have. Sophomore year, I wasn’t that smart about it, but those experiences in sophomore year led me into junior year where I could figure myself out in terms of drinking.”

She says that she began using alcohol after returning from a trip in the summer before sophomore year, claiming that exposure to a different culture overseas—as many countries have legal drinking ages between 16 and 18—caused her to start drinking back home.

“After I came back, it didn’t seem like that big of a deal to me,” she said. “I wasn’t really getting drunk, it was more just social— I didn’t feel like I was doing anything wrong necessarily.”

She kept drinking with friends, and her consumption slowly escalated over time. She first remembers getting drunk during the second semester of her sophomore year, an experience that she attributes to peer pressure from a group of friends that partied more frequently.

But a year later—nearly two years after she had first used alcohol—things hit a stopping point.

“I was at this party, and I got really drunk, and I threw up,” she recalled. “That was the only time I ever threw up from alcohol, and it was like, ‘Never doing that again.’ Obviously I didn’t enjoy it— when I get pretty drunk, I kind of realize that I’m not myself anymore, and I get a little paranoid and scared.”

The story runs differently for the sophomore male, however. Two years after his first incident of substance abuse, his usage increased. He claims that he began drinking alcohol, and taking what are known as “Pokeballs”: tiny, circular pills that are supposed to contain nearly pure ecstasy.

Just like the senior female, he found the experience unsettling at first, but his eventual reaction was different.

“The first time I popped a pill I was freaking out— it was a little scary,” he remembered. “But then it was fun after.”

His involvement with these drugs ran further. He says that he began buying the pills from a friend—who also produced them—and selling them for profit. He claims to buy a “roll” of 100 pills for about $200 or $300, keep 10 for himself, and sell the rest for four times what he had originally paid.

He believes that herein lies the explanation for his increasing drug abuse. Knowing the friend who made the Pokeballs led him to the drug—an explanation strikingly similar to that given by the senior female regarding her first two years using alcohol in increasing quantities.

“As you get older, you meet new people,” the sophomore male said. “I wouldn’t say it’s so much just about [being in] high school.”

Programs and advice

When new survey data is released, administration discusses the issues at hand and the best ways to get their message out to students.

“For example, would it be my place to best address the use of drugs and alcohol?” Scott said. “Probably not, because I can’t reach 2,500 students. But there are biology classes and physiology classes and P.E. classes that talk about health on a regular basis. So they can take those aspects of that survey and best address them.”

She believes that one of the most effective ways to reach students is through programs such as the “Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids,” which comes to MVHS each year with BMX bikers and skaters. Though the lunchtime activity focuses on tobacco products and not illegal drugs, Scott thinks that it is important to emphasize that students can be “cool” without substance abuse.

Yet despite administration’s efforts to prevent alcohol and drug use amongst students, the sophomore male is still skeptical.

“I can almost guarantee you that the school knows who [uses and sells drugs],” he claimed. “If the objective was to crack down on these guys, it could have been done a long time ago.”

Assistant Principal Brad Metheany, who often deals with discipline in substance abuse situations, disagrees strongly. He points out that, about once every three weeks, the school is forced to call the sheriff because a student is in possession of controlled substances at school.

“We hear that a lot—there’s no question that people think that we’re doing nothing,” Metheany said, “and that’s not the case. We always investigate [substance abuse situations.]”

Metheany also responded that he personally disagrees with policies such as regular searches of suspected drug users; “This isn’t a police state,” he emphasized.

But regardless of punishment, the senior female advises against drinking alcohol in excess, or using marijuana—which she tried once—because people who do so are no longer themselves. For the same reason, the sophomore male discourages others from popping pills—”They do messed up stuff to your brain,” he explains.

And as he left our D-building corridor, fighting the wind on that stormy day to return to his friends in the bustling shelter that was the cafeteria, the sophomore male wasn’t alone. He was just one of the estimated 3,000 FUHSD students who have used alcohol or drugs.

Each another story. Each another rap sheet.

Each another person for the schools to reach.

Sidebar: The school’s place in substance education

As clear-cut as the disciplinary rules are, there is disagreement over the school’s ideal role in terms of drug prevention programs. The sophomore male, a drug user wvho spoke to El Estoque on the condition that his name would not be used, objects to these programs, taking issue with how negatively alcohol and drugs are portrayed.

“Not that drugs are safe at all—obviously there’s consequences—but you can be smart about it,” he said. “I’m not going to take two pills and get drunk and run across the street and get run over— I feel like [the school] exaggerates about how severe drugs can be.”

The senior female, an alcohol user who also spoke to El Estoque on the condition that her name would not be used, believes that some of MVHS’s anti-substance abuse assemblies in the past were perfectly within the school’s role, but understands how things might have to be overstated.

“I don’t think it’s the school’s place to say, ëHere’s how to be safe with alcohol,'” she explained. “That’s definitely the family’s place— a school shouldn’t be saying, ëIt’s okay to drink.'”

Unlike the sophomore male, who has kept his drug usage secret from his family, the senior female is very truthful with her parents and sister about alcohol. She calls her parents “open-minded,” claiming that they are okay with her drinking in moderation.

She explains that this has created a trusting environment, making her drinking practices much safer. When she goes to a party, she tells her parents where she is going, if she will drink, and if she needs to be picked up afterwards.

For this reason, she is annoyed by certain in-class discussions on alcohol and drugs, because she believes that the issue is best resolved in the home, not the classroom.

“I think that if a teacher is really adamant about it, then they are crossing the line,” she said. “I think that’s overstepping a parent’s or family figure’s role. It’s really not their place to say what you can and can’t do.”

Scott understands that family may be a large factor in preventing substance abuse, but sees things from a different perspective when it comes to school involvement.

“It’s a partnership, and number one is the home—the family setting the model, and the morals, and the values for the students,” Scott said. “But we have to talk about the health issues—drugs and alcohol being two aspects of that—what the negative ramifications are, and how students would be healthier human beings without them.”